Corp Governance: The Achilles' Heel of "High Quality" Companies

Lessons from Relational Investors and Governance Pioneer Ralph Whitworth

Welcome to the Nongaap Newsletter! I’m Mike, an ex-activist investor, who writes about tech, corporate governance, the power & friction of incentives, strategy, board dynamics, and the occasional activist fight.

If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, I hope you consider joining me on this journey.

Great businesses do not always generate great stock returns.

There are several reasons why this happens, but more often than not poor corporate governance is a major contributing factor.

Corporate governance is the achilles’ heel of “high quality” companies.

All of us (I hope) understand the importance of corporate governance, but I think few truly appreciate (or realize) the compounding effect corporate governance can have (both good and bad) on stock returns.

I learned this lesson first-hand as an investment analyst at “friendly” activist fund Relational Investors where we (generally) worked behind-the-scenes with companies to implement good corporate governance practices to drive outsized, compounding stock returns. They didn’t all turn out that way, but that was always the goal.

For this newsletter, I wanted to share a few lessons I picked while at Relational Investors, and explain why I think good corporate governance is one of the most underrated moats out there.

Photo: Relational Investors boardroom. Home to many of my investment lessons.

Relational Investors: Pioneers in Activist Investing

Relational Investors was founded in 1996 by Ralph Whitworth and David Batchelder who previously ran T. Boone Pickens’ corporate raiding operations in the 1980s. As noted in the New York Times (1988):

When the definitive history of Wall Street is written, Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc. is assured a place as the house that built the junk bond. But had it not been for David H. Batchelder, adviser to the Texas oilman T. Boone Pickens, the age of the junk bond might well have arrived much later.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that many prominent activist investors (Icahn, Rosenstein, Peltz, etc) cut their teeth in the Michael Milken junk bond fueled M&A boom. Activist investing was a natural segue for many of these investors.

Relational Investors was the first “activist fund” seeded by pension giant CalPERS as a way to “fix” corporate governance. Although CalPERS’ public equity exposure was mostly passive, they wanted a way to advocate “good” corporate governance practices and created the “Relational Investing” program as a result (which is where the name Relational Investors took inspiration from).

Over the course of ~18 years, Relational ended up conducting over 100 “activist” projects and joined over 20+ public company Boards including Home Depot, Waste Management, HP, and Intuit. At its peak, the fund managed over $8 billion.

The influence of Relational went beyond their portfolio engagements as companies began to preemptively implement learnings from past activist engagements to thwart future confrontations. Relational really was a “governance lab” with many concepts advocated by Relational now considered governance “best practices”.

In 2014, Relational announced that Ralph Whitworth would go on indefinite medical leave and dissolve the fund as a result.

Overall, I was at Relational from 2006 to 2014 (both as a generalist and covering tech) where I was a fly-on-the-wall for some of the most interesting activist and corporate governance situations in Corporate America.

So if you’ve wondered why I know corporate governance “Dark Arts” so well or why I have a knack for sniffing out material events by “reading the man and not the cards”, it’s because I’ve spent much of my professional investing career trying to understand, anticipate, and counteract bad governance practices.

Relational Investment Strategy

Relational took a very concentrated portfolio approach (fewer than 10 to 15 names) and the type of company Relational pursued was conceptually straightforward:

“We look for companies that are trading at discounts to their intrinsic value—despite the fact that they have low financial leverage, strong defensible core businesses, and growing cash flows. Invariably this discount exists because investors do not expect management to effectively reinvest the projected profits. This negative expectation is typically caused by a poor history of investment outside of the core franchise and/or from chasing growth within the core franchise in the face of maturing industry conditions.”

- Ralph Whitworth (Interview)

Basically, Relational was looking for “high quality” companies with terrific cash flowing assets, but the market was punitively discounting their incremental capital allocation.

This punitive discount was usually due to a history of poor investments (i.e. awful M&A, several failed speculative bets, low “hit” rate on core innovation spend, etc.) and/or poor investor communication on what the Company is trying to accomplish with their incremental spend.

Bad Capital Allocation Destroys Value

Poor investment decisions were typically driven by management teams chasing growth (“We must innovate and grow!”) in hopes of ramping up the Company’s valuation multiple.

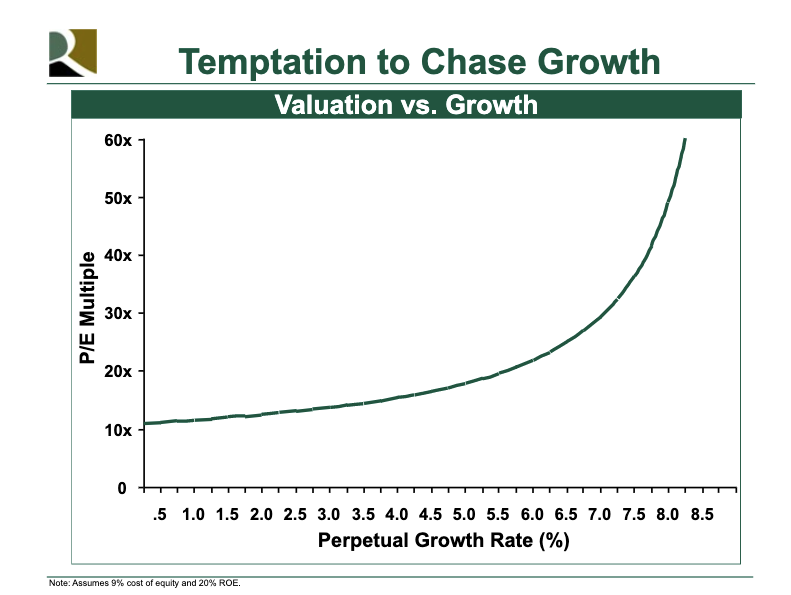

Mind you, I’m not saying pursuing growth is bad. There is definitely a non-linear relationship between growth and the valuation multiple the market is willing to pay for that incremental point of growth.

The issue is management teams will pursue these growth initiatives without considering or contemplating returns and destroy shareholder value in the process.

Relational believed that if a Company can be more thoughtful with their capital allocation and investor communications, the gap between market value and intrinsic value would close and the stock could become a market outperforming “compounder”. (We didn’t actually use the phrase “compounder” but it’s popular lingo today and captures what we were trying to accomplish.)

Yes, Relational also pursued event-driven activist situations (M&A, consolidation, spin-offs, etc.), but I’d say the bread-and-butter was working with companies behind-the-scenes on governance and capital allocation issues.

Relational Engagement Process

What was unique about the Relational investment process was the fund showed up on day 1 presenting management with a plan to “unlock value”:

“We map out an engagement program prior to making our initial investment. We try to gauge the likelihood of change and potential upside. Typically before we meet with management, we’ll buy some sort of toe-hold in the company.”

- Ralph Whitworth (Interview)

In hindsight, the “first meeting” can be a pretty jarring experience for the CEO.

Although Relational had an engagement program, this doesn’t mean management was told what to do or threatened (i.e. stop growth investing and do a levered buyback or we’ll get rid of you). These engagement plans were recommendations based on Relational research and feedback/pushback was welcomed (seriously).

Relational used these engagement plans to start a healthy dialog with the goal of building consensus and accountability to close the gap between market value and intrinsic value.

The Importance of Corporate Governance

Corporate governance was an incredibly important factor (and lever) in the engagement plan:

“Corporate governance is a major factor in our investment decisions for two overarching reasons. First, we are convinced that corporate governance practices and policies, as well as those of executive compensation, materially impact the performance and, therefore, the value of corporations. Second, since each of our investments involve an engagement plan to influence change, we must understand how the particular governance features of our portfolio companies will impact our efforts.”

- Ralph Whitworth (Interview)

Bad capital allocation doesn’t kill a Company’s valuation. Markets will actually tolerate quite a bit of (failed) risk-taking before a punitive valuation is applied.

It’s the persistence of bad capital allocation, along with the perception of poor (or haphazard) decision-making, and an unwillingness to “course correct” that really drives discounting.

Relational believed the cause of this “persistence” is usually due to bad corporate governance and not driving accountability with management.

Often times, implementing “good” corporate governance involved reseting the power dynamics on the Board (i.e. truly giving all Directors a voice) and having those (positive) structural governance changes and accompanying decisions cascade down the organization.

When this occurs, markets begin to appropriately value the company’s “high quality” assets and decision-making.

“High Quality” Compounder Stocks

Morgan Stanley (pdf file) defines “compounder” stocks as:

High quality companies that can consistently compound shareholder wealth at a superior rate over the long-term, while offering relative downside protection.

That’s pretty vague, but in general I think the term “high quality” is a catchall for companies that possess:

A durable/defensible franchise (open to interpretation)

Strong cash flow generation and ROIC

Low capital intensity

Excellent unit economics

Pricing power

Preferably recurring revenue

Large addressable markets

Reinvestment runway

“Friendly” activist fund ValueAct Capital has a nice snapshot of characteristics “high quality” companies possess (2013 presentation):

It’s an old slide but I like it for a couple reasons:

It captures many of the enduring “high quality” characteristics investors look for.

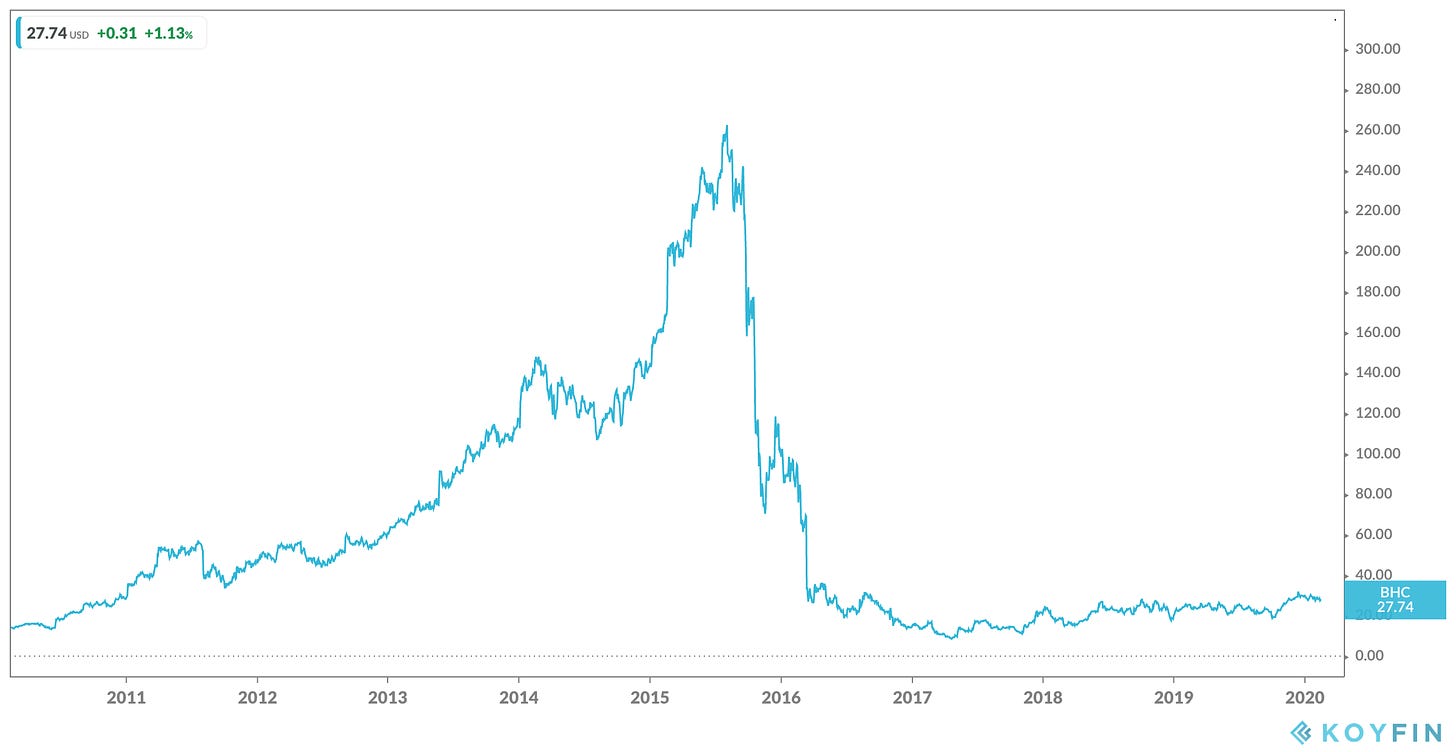

It features Valeant (now Bausch Health) as a “high quality” company.

This isn’t a knock on ValueAct (who is doing insanely well and shouldn’t care what this little newsletter says about them anyway) and we have the luxury of hindsight, but this slide shows how poor corporate governance can be a blindspot for many investors who look for “high quality” compounders.

Bad decisions, loose incentives, and short-cuts are always tolerated (or overlooked) on the way up, but those issues never really go away.

Often times, they compound and accumulate (like bad governance debt) until the problem can’t be ignored and the stock unwinds.

Corporate governance is the achilles’ heel of “high quality” companies.

When it “snaps”, it doesn’t matter how healthy the rest of the business is. The Company will remain immobile and ineffective until major repairs are made to governance.

Compounding Effect of Corporate Governance

Valeant represents an exaggerated example of corporate governance being a blindspot for investors, and the compounding effect bad corporate governance (i.e. bad incentivizes) can have on a stock.

The unwind might not happen right away, but eventually the weight of bad corporate governance will inflect a Company’s trajectory downward.

By the way, bad corporate governance does not mean bad Directors. A lot of scandals in history and fundamental problems leading up to financial crisis can be traced back to boards consisting of good people, with good integrity, and high intelligence but for some reason the Board dynamics were such that the Directors weren’t reacting to strong signals and not asking the right questions.

On the flip side, investors also don’t fully appreciate the compounding effect of good corporate governance and the impact that can have on a stock over a prolonged period of time.

I think the reason it’s not fully appreciated is because the “value add" of good corporate governance is not clearly attributed in the P&L. It can be hard to quantify the value attributed to good corporate governance.

For example, most employees love steady stock returns brought on by sound capital allocation principles, and appreciate clear communication at the top. This creates a lower churn environment where employees know what is expected of them and can buy into the Company’s vision.

Good corporate governance also attracts thoughtful, long-term orientated shareholders, and improves the talent base as more high-performing talent joins the Company.

After a few years, with an employee base that’s “bought in”, patient investors, and an improved talent base, the Company commands a valuation premium and management actually has more leeway to take on more risks (without the punitive valuation hit). Furthermore, the Company can now pursue and execute on growth initiatives that was previously not possible (maybe the talent wasn’t available before).

Also, when there’s a market downturn and high uncertainty, investors will seek out the Company (“flight-to-safety”) due to its reputation as thoughtful stewards of capital and provide downside protection on the stock.

Like I said, good corporate governance is an underrated moat.

Let’s walk through a couple specific Relational investment cases to really drive home the point.

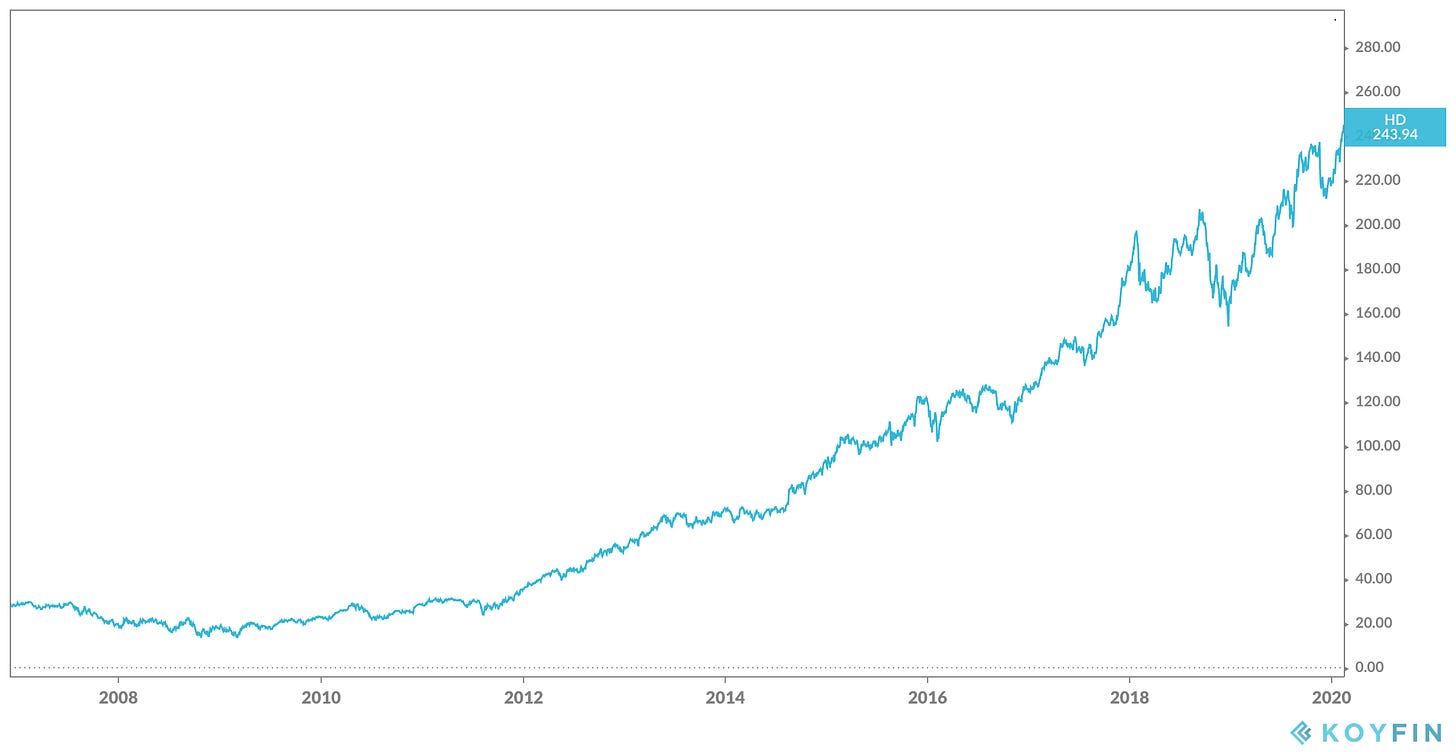

Home Depot

Relational’s David Batchelder joined Home Depot’s Board in February 2007 with the goal of addressing the following issues:

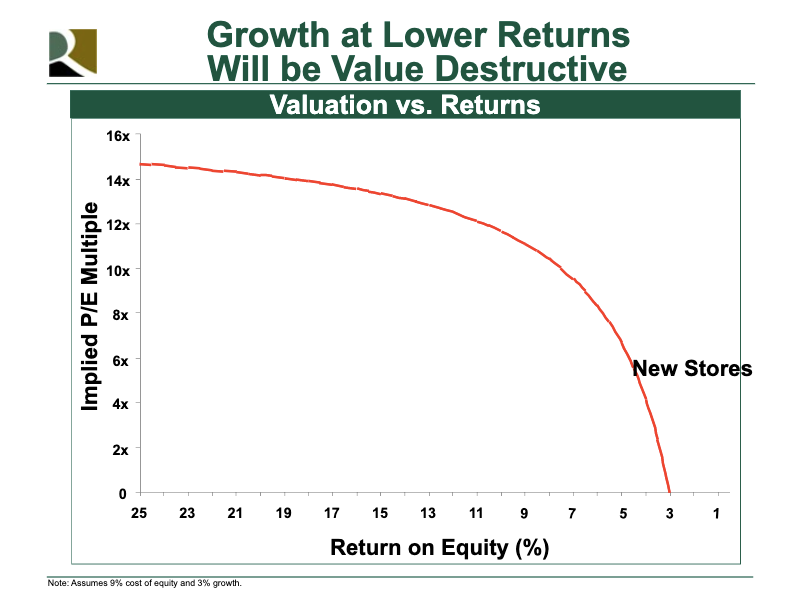

Home Depot was chasing growth and opening new stores that were generating returns below their cost of capital.

The Company expanded into the wholesale business by acquiring their way into the business with returns of ~8% (below their cost of capital).

Hindsight Note: I know it was a controversial decision to get out of wholesale business, but you have to put that decisions into context given all the other more pressing issues the Company needed to be prioritize.

Home Depot had been squeezing profitability from their retail stores by reducing staff and underinvesting in distribution and IT.

As part of the Home Depot turnaround, Relational worked with management to refocus on improving the in-store experience and improve store-level economics:

Batchelder and his Relational Investors team, based in Del Mar, California, provided [CEO] Blake and the board with critical data and analysis which convinced the board that further store expansion should be all but halted.

Instead, Blake and the board determined that within-store returns should be emphasized, requiring drastic reductions in inventory and equally dramatic improvements in customer service, incentive systems, and employee morale.

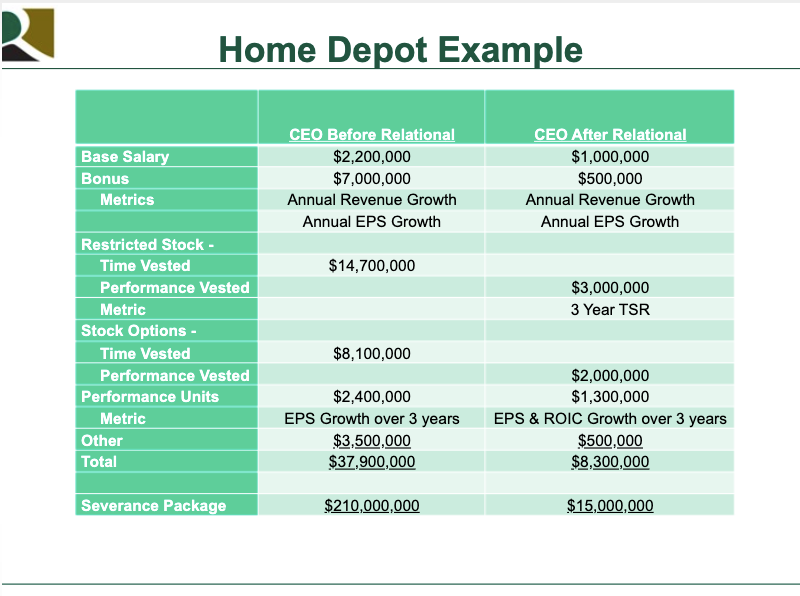

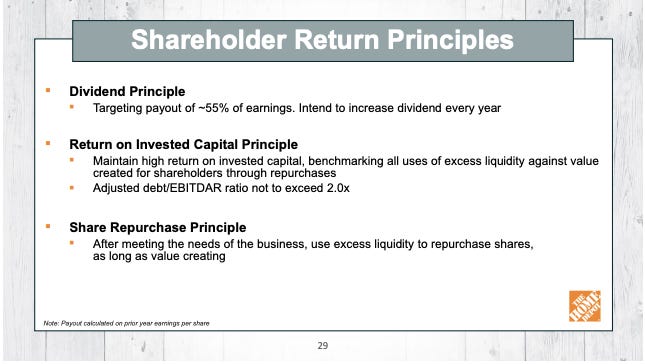

Home Depot also overhauled the executive compensation program to include ROIC and Total Shareholder Return (TSR) components to drive better alignment between growth and returns:

Finally, a new disciplined capital allocation framework was implemented and communicated to shareholders. Nearly a decade after Relational’s involvement, the corporate governance and capital allocation principles advocated by Relational persists today:

Incidentally, David Batchelder is now on the Board of Lowe’s and I suspect he’s implementing similar concepts there.

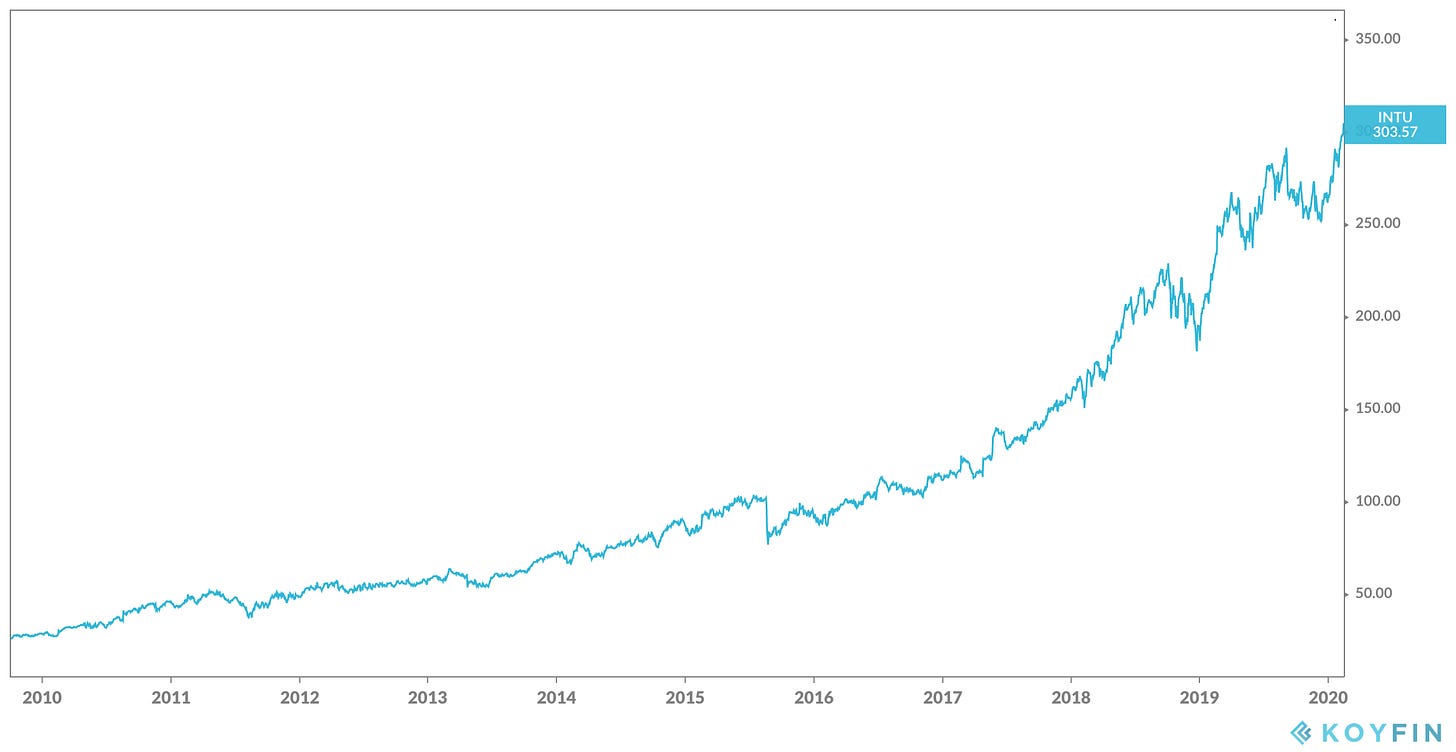

Intuit

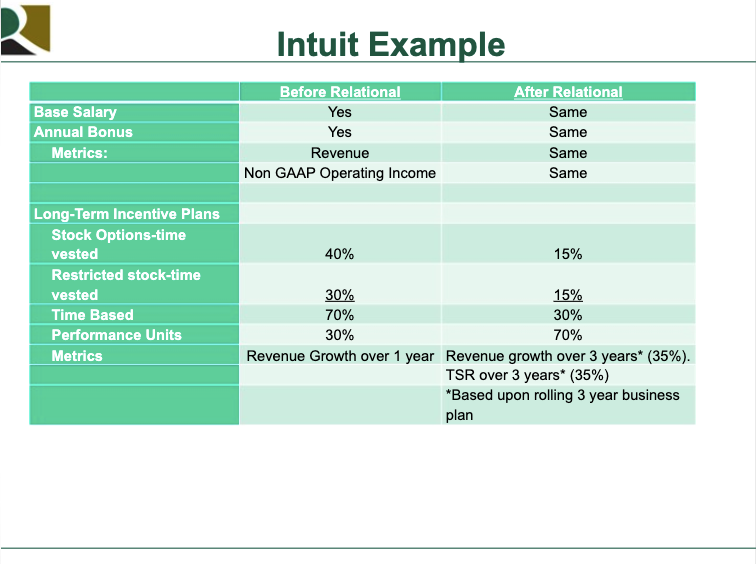

Relational’s David Batchelder joined Intuit’s Board in October 2009 with the goal of addressing the following issues:

Intuit’s executive compensation program was tied to 1-year financial goals without consideration for returns (i.e. chasing growth without considering returns). To better align incentives, a significant portion of equity compensation was tied to a 3-year operating plan and total shareholder returns (TSR)

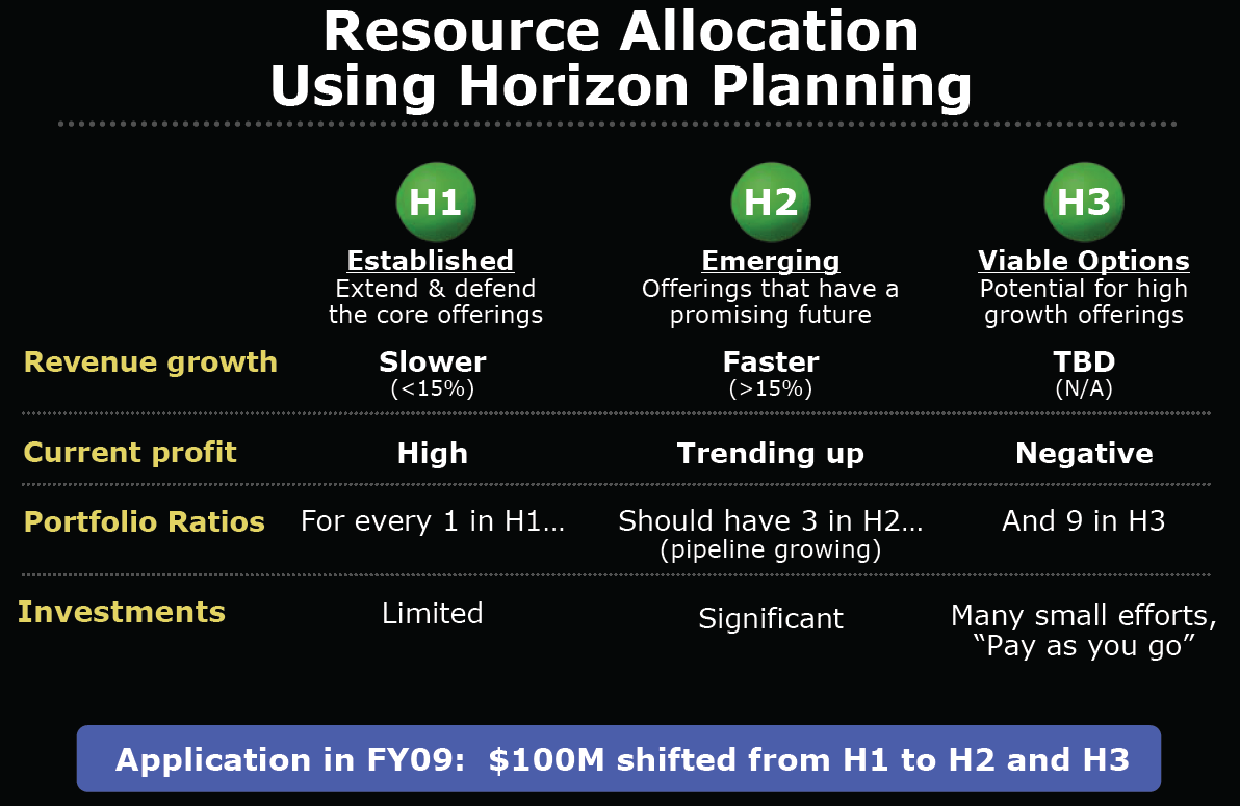

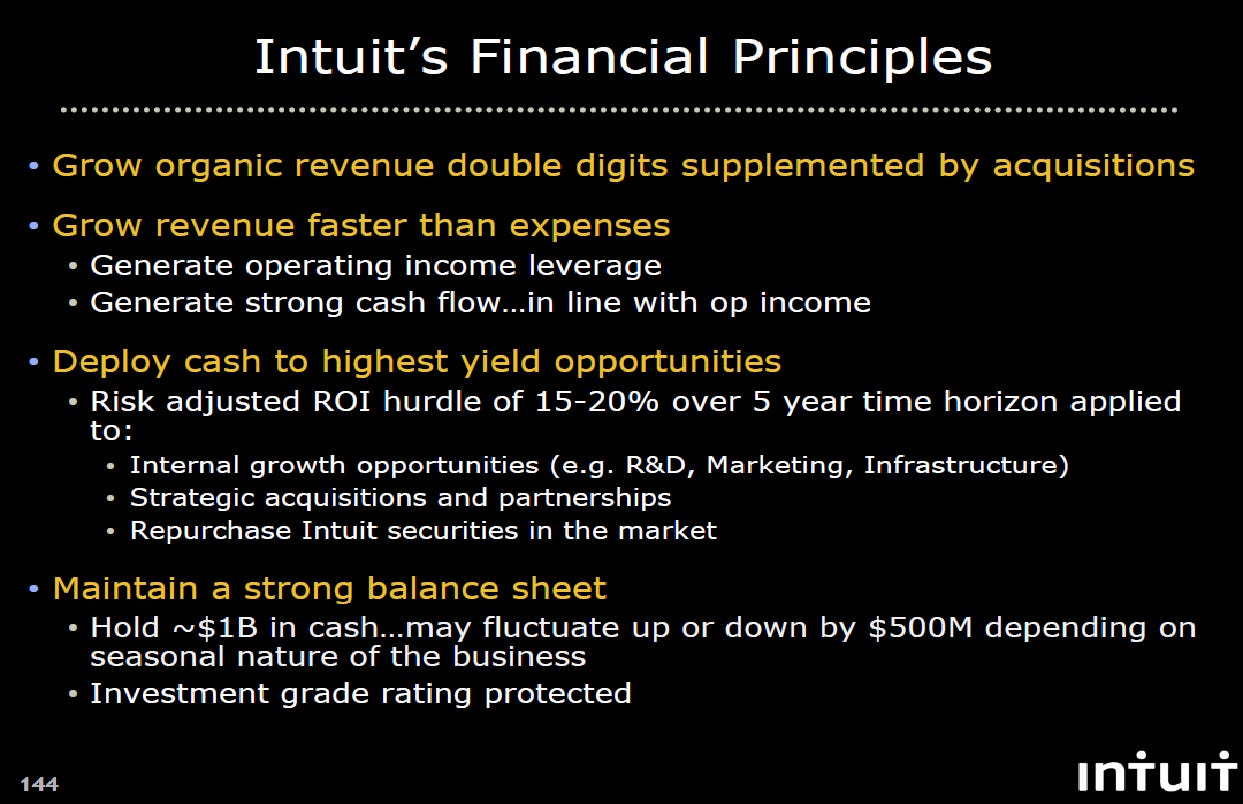

Prior to Relational’s involvement, Intuit had a vague capital allocation philosophy tied to revenue growth with no clear quantitative ROI hurdles. (2008 Investor Day Slide)

A new capital allocation philosophy is implemented and communicated to shareholders with ROI hurdles and long-term operating model targets. (2009 Investor Day Slide)

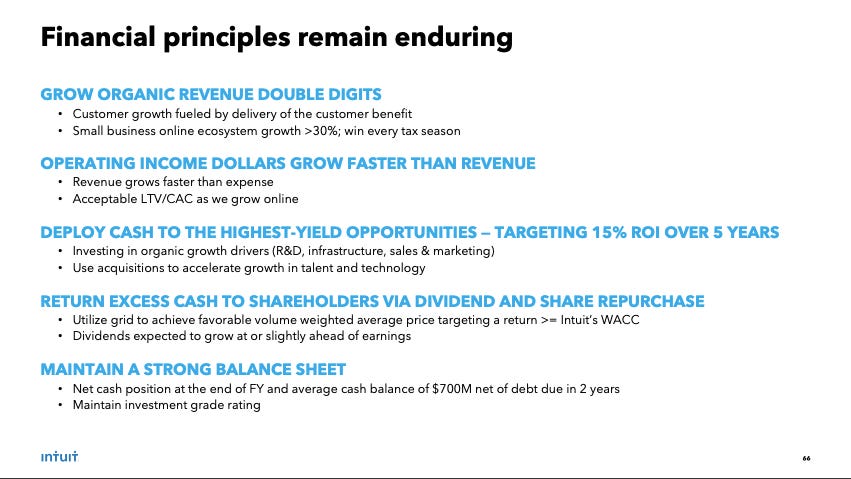

10 years later, Intuit still adheres to financial principles advocated by Relational Investors. (2019 Investor Day Slide)

Ralph Whitworth “Investor Perspective” Interviews

I’d be remiss not to have a section dedicated to Ralph Whitworth. I previously wrote about Ralph in Dozen Things I learned from Ralph Whitworth on Investing, Activism, and Business, and many of the concepts I’ve shared in this newsletter are based on Ralph Whitworth’s governance philosophies.

Photo Source: InsiderMonkey

Although he is no longer with us, his legacy lives on in the corporate governance “best practices” he’s advocated for much of his career.

There are a couple wonderful interviews I wanted to highlight and summarize Ralph Whitworth’s governance philosophies:

Next Generation of Board Leaders

Summary:

Boards need an investor perspective.

It’s shocking that Fortune 100 companies don’t have an analyst within the company that is analyzing the company from the “investor perspective”.

Traditionally, when people talk about the investor perspective, it’s often the investment banker that services the company or a retired banker.

Investor perspective is not about investment bankers. It’s about actual investors or someone that has been recommended by an investor and sees themselves coming from that investor perspective.

The investor perspective will become more and more important over time.

One area lacking in the boardroom is someone who in a deep way understands how to present and communicate company assets in a public market.

There’s been a shift since the 1960s where 10% of the outstanding shares were held by institutional investors (fiduciaries). Today it’s approaching 70%. That shift has taken place but we haven’t seen the same shift in the boardroom. Directors are largely sourced in a similar (1960s) way and come from similar pools.

Investors have been able to nominate directors since 1992. Before that, you had to change to whole slate or no slate. Ralph came up with shareholder access in 1989.

Troubled with the retirement age issue (artificial way to force turnover)

To expand addressable pool of Directors, Ralph Whitworth always recommends:

Not requiring previous Board experience.

Don’t have to be a CEO of a public company.

As soon as you do that, suddenly the issues of glass ceiling and diversity go away and you open up a field of eligible Directors. We can afford to have a few folks on the Board who don’t have that experience (obviously do the appropriate vetting).

Look at the Board composition in a dynamic way. Committees are taking a narrow view on addressing vacancies on a year-to-year basis instead of taking a 5-year outlook and setting criteria and objectives on that basis. You begin to realize there are actually 4-5 “vacancies” on any Board.

Don’t think it’s a good idea to ask the CEO who they want on the Board. Be mindful of search firms seeding candidates from CEOs.

CEOs will push hard on who should be chair of the compensation committee.

Really have to watch the Board dynamics.

Investor perspective is not Wall Street perspective. It’s about Omaha perspective. San Diego (Relational) perspective. Atlanta perspective. Get away from the classic Wall Street investment banker hanging out in the Board room.

One or two people can completely change the board dynamic.

Ralph Whitworth Interview

Pioneer in the “activist investing” approach.

Projects involves an investment we make where we think we could become part of the value proposition.

Polite knock on the door. Request for meeting and a few recommendations (at this stage, the recommendations are more set up as challenge so we can get the feedback and validate the thesis around the company).

Of the 100+ projects, you’ll only see a dozen or so public campaigns. Work behind the scenes and not out in the press. Constructive series of communications.

Corporate America has done a poor job of managing optics and managing the practical aspects of compensation. The escalation of compensation is the smoking gun that something is wrong in the boardroom and something wrong in governance systems.

Focus on the dynamic in the boardroom. It’s human nature when you’ve been chosen by a certain group and to go along with that group. A lot of scandals in history and fundamental problems leading up to financial crisis can be traced back to boards consisting of good people, with good integrity, and high intelligence but for some reason the dynamics were such that they weren’t reacting to strong signals and not asking the right questions.

Do we have a devils advocate? It is an important dynamic to the Board.

Make sure independent directors are acting independent.

Make sure you’re using your time right and managing your time. This is something Boards do the poorest. They defer too much to the general counsel’s office or management to set the agenda for the Board meeting and they come in and they’re just reacting rather than setting up a situations where they can be proactive.

Great Boards structure their time well.

Encouraged that Boards are more responsive to investors and more quick to react when things are drifting in the wrong direction.

Composition of Boards aren’t shifting fast enough away from legacy models. Shareholders need to be a bigger part of that process.

Premium

Thanks for reading!

If you’re interested in content that takes this “investor perspective” approach to critiquing capital allocation, corporate governance, and company analysis, I hope you consider the premium newsletter.