How to G.O.V.E.R.N.

A framework to examine & integrate corp governance into your investment process

Welcome to the Nongaap Newsletter! I’m Mike, an ex-activist investor, who writes about tech, corporate governance, the power & friction of incentives, strategy, board dynamics, and the occasional activist fight.

If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, I hope you consider joining me on this journey.

A Framework to Examine & Integrate Corporate Governance into your Investment Process

Note: Election day is upon us. A big day for governance. Don’t worry, this isn’t a political post.

A few folks have reached out asking about ways to integrate corporate governance research into their investment process. While I generally believe you need to develop your own governance research process that fits your investment process, I figured I would share my high-level feedback and suggestions.

This framework is very generalized and isn’t meant to be thorough. The goal is to provide you with the concepts I consider important.

G.O.V.E.R.N. Framework

What’s the point of sharing a framework if you don’t give it a catchy name?

I’m calling this the G.O.V.E.R.N. framework.

The G.O.V.E.R.N. framework categorizes corporate governance into 6 factors/buckets:

Greed

Opportunity Costs

Valuation

Executives

Referendum

Narrative

Keep in mind these categories influence one another and overlap, especially around compensation. Actually, I’d consider compensation the nexus that brings G.O.V.E.R.N. together.

This framework isn’t meant to be a “check-the-box” exercise, and requires thoughtful research to properly connect-the-dots.

Let’s dig in!

Greed

It’s important to understand what insiders are “greedy” about, because that’s going to heavily influence incremental decision-making. As the saying goes, incentives drive outcomes.

Let me emphasize that “greed” is not a good or bad in corporate governance. Context matters and “greed” can be incredibly helpful in one situation and terrible in another.

In general, the desire to get paid is a major driver in corporate governance, and there’s a wide range of “greed” to consider.

Some insiders, like VC or PE directors, will be greedy about exiting their large stock holdings and advocate decisions that favor near-term price action at the expense of long-term priorities. Those same investors may also have “franchise greed” and advocate decisions that is detrimental to the company, but protects the investor’s franchise and/or other economic interests.

Some insiders will also be greedy about power and reputation, and will maneuver to maintain and grow standing both within and outside the company. For instance, a director who maintains a reputation for “not rocking the boat” can open up additional directorship and executive opportunities.

Greed can also be expressed in capital allocation decisions (i.e. hoarding cash, empire building) and in misaligned compensation incentives that pays management disproportionately relative to company performance.

Your goal is to understand, to the best of your abilities, what insiders are “greedy” about, because it will inform how they approach incremental decisions. From there, you can risk-adjust and assess how those incremental decisions will impact shareholder value.

And finally, we can’t talk about greed and not mention the “Dark Arts” series:

If you’re new to the “Dark Arts”, I highly recommend reading Part 1 which provides a pretty thorough run down of the basics and high-level concepts.

For Part 2, I walk you through a case study that features TPG, their co-CEO Jim Coulter, and the infamous acquisition of J. Crew.

For Part 3, I cover Stamps.com (ticker: STMP) and walk you through the company’s legendary (to me) 2019 options grant to management.

For Part 4, I show you how I develop a “big picture” view of proxy disclosures and critique GreenSky’s (ticker: GSKY) aggressive equity grant practices.

For Part 5, I discuss Kodak and how directors double dipped on equity grants, and granted options to management a day before announcing a $765 million government loan that would pop the stock from ~$2.50 to ~$33.

Aggressive equity grant practices is a systemic and well-protected way to express “trembling with greed” without the scrutiny and prosecution of insider trading. Also, changes in compensation and/or equity grant practices can offer strong signals on insider sentiment and performance expectations.

Opportunity Costs

Governance is in many ways about managing opportunity costs and trade-offs. By understanding opportunity costs and trade-offs, you’ll better understand why certain governance and strategic decisions are made.

It should not come as a surprise that “greed” and “opportunity costs” have a lot of overlap.

It’s important for investors to review corporate governance and ensure they’re incentivizing and encouraging the right opportunities and balancing trade-offs. Otherwise, there’s risks that governance decisions will disproportionately favor insiders by narrowing their opportunity costs (especially around compensation) at the expense of widening the opportunity costs for shareholders and destroying long-term value.

A classic example of this is executive compensation getting structured in a way that economically discourages management from exploring strategic alternatives to the detriment of long-term shareholder value.

Another example is decoupling compensation from punitive capital allocation decisions (i.e. bad M&A) to ensure management maintains upside if an acquisition works out while protecting their economic downside if it doesn’t.

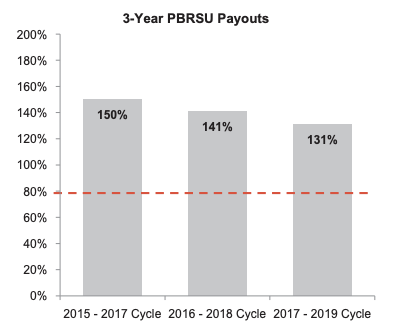

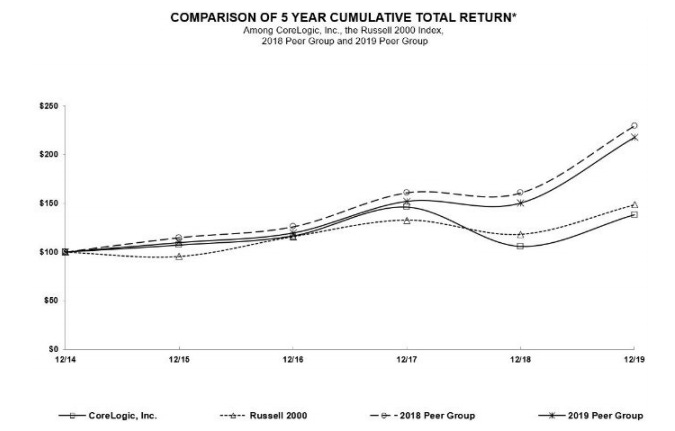

Both of these dynamics can be seen at real estate data and analytics provider CoreLogic where the Board rewarded generous 130%+ payouts on performance-based RSUs by using (in my opinion) easy-to-achieve adjusted EPS targets:

During the same performance period CoreLogic insiders were getting paid 130%+ equity payouts, the company materially lagged their compensation peer group:

This generous executive compensation structure at CoreLogic removed the incentive and sense of urgency to acknowledge lagging returns and consider strategic alternatives to enhance shareholder value. It required a hostile bid from Bill Foley to finally force CoreLogic to address their issues.

Alternatively, compensation can be materially adjusted to encourage a transaction via favorable vesting terms and/or equity composition. An example of this can be seen at Instructure where the Board granted front-end loaded equity to management while receiving inbound acquisition interest:

The [Instructure] Board approved the new front-end loaded multi-year equity grants on January 23, 2019 when the stock was at $39.30 with full knowledge that a $53.00 to $55.00 per share offer was on the table.

Overall, best-in-class Boards do a great job of managing opportunity costs and alignment. This is the heart of a great capital allocation program, and if your investment process prioritizes capital allocation “quality”, it is essential you understand how a company’s corporate governance manages opportunity costs and drives disciplined capital allocation.

Valuation

Personal opinion, but there’s reflexivity in stock price and decision-making.

When a stock is running, it’s going to influence how management prioritizes capital allocation and ROI considerations. It’s only natural for companies to consider using their rich stock valuation to pull forward their roadmap via M&A, aggressive capex, etc.

Boards will also accommodate this aggressiveness by adjusting compensation to encourage more risk-taking and change the composition of equity compensation to ensure payout (i.e. swap options out for performance shares with achievable hurdles).

On the flip side, a stock that has experienced a material sell-off may force a reset in strategy and operating plans. It forces the company to re-focus and reset compensation to align with new priorities.

When it comes to valuation, it’s always important to monitor what adjustments are made to compensation in response to material changes in valuation. Boards will often signal their go-forward intent through compensation changes, and those adjustments will be influenced by greed, opportunity costs, executive dynamics (see “Executives” section), and feedback loops (see “Referendum” section).

Needless to say, 2020 has been a boom year for these sort of adjustments and has been featured constantly in the premium newsletter.

Executives

There’s a popular idea in software called Conway's law that states:

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure.

Corporate governance isn’t software, but I believe follows this concept.

Essentially, a company’s corporate governance structure will resemble the communication and organizational power structure that produced it.

If you believe this is true, then examining a company’s corporate governance structure and governance practices, especially around compensation, will tell you a lot about the executive team, their values, and the power dynamics at the Board.

It will also help you figure out if the management team can be trusted as stewards for shareholders, and flag egregious principal-agent risks. If your investment process focuses on management “quality”, it is essential you understand and nail this.

I could really go down the rabbit hole on this (as seen in my e.l.f. Cosmetics write-up), but I’d say if insiders aren’t engaged in egregious “dark arts” practices you’re generally going to be ok. That said, I’d also keep an eye on the Board aggressively moving the goalposts on compensation metrics in management’s favor and overly catering to their preferred strategy. That set up tends to produce a languishing stock.

Referendum

Corporate governance offers some interesting feedback loops that investors can leverage into their investment process, especially around director elections.

Speaking of elections, what’s interesting about Presidential elections is they also serve as a major referendum on governance the past 4 years and what should be prioritized going forward.

Incidentally, many public companies go through a similar referendum cycle. Every 4 years or so, there’s usually a “referendum” on management, their current strategy, and company priorities. This “referendum” can be expressed explicitly with the arrival of an activist and a contested election or implicitly via stock price performance which typically causes reflexive changes.

Referendums are also expressed through “withhold” (or “vote no”) votes of directors, and significant shareholder turnover.

I believe it’s important to examine how management and the Board responds to these “referendum” feedback loops. Are they fighting negative feedback and entrenching themselves or are they being responsive by reseting priorities, objectives, and compensation goals?

If feedback is really positive, does that embolden them to take excessive risks or bring about complacency? Sometimes stock performance is so good that investors will overlook massive red flags and terrible governance which leaves the company vulnerable to future blow ups.

Overall, I think many thoughtful investors have a good handle of operational feedback loops (i.e. flywheels). The next step is to understand how corporate governance feedback loops positively and negatively influences the company’s operational feedback loop.

Narrative

Finally, I think it’s essential to figure out what is the narrative the Board is trying to communicate about the company. That narrative is going to heavily influence the company’s governance and compensation decisions. It is also going to push the company into pursuing an operating plan that applies this narrative as the “North Star”.

The question is, can management execute towards this desired narrative? Is the business suited for that narrative? How does the Board drive accountability?

A material mismatch between the Board’s desired narrative and what the company has demonstrated it can reasonably achieve is a recipe for years of mediocre/bad stock performance and shareholder frustration. To make matters worse, the Board not being pragmatic can also defer necessary “hard decisions” for years.

That said, narrative is probably my favorite factor to spend time on. If you can recognize and/or anticipate the Board and management is about reset around a realistic narrative, significant risk-adjusted returns are available. And unsurprisingly, changes to compensation can be the “canary in the narrative coal mine”.

Conclusion: Compensation is the Nexus

Spend enough time researching corporate governance and applying the G.O.V.E.R.N. framework, you’ll quickly begin to realize compensation is the nexus. Many of the important signals needed to makes sense of things are found in compensation.

In particular, I love applying this framework to compensation where insiders receive equity with price-based vesting conditions.

Why? Price-based vesting isn’t done by happenstance. Boards and management teams don’t blindly implement price-based vesting, and are typically adopted with specific goals and plans in mind. If you can deduct what those goals and plans are, compelling risk-adjusted investment opportunities await.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading and hopefully you found this helpful.