Welcome to the Nongaap Newsletter! I’m Mike, an ex-activist investor, who writes about tech, corporate governance, the power & friction of incentives, strategy, board dynamics, and the occasional activist fight.

If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, I hope you consider joining me on this journey.

In this multi-part series, I’m going to show you how people use the “Dark Arts” of corporate governance to:

Take Advantage of Unsuspecting Shareholders and Directors

Influence Decision-Making

Profit

And yes, if you know what you’re doing, there are windows of opportunity to participate alongside.

Why am I sharing the “Dark Arts”?

Because it’s the best way to expose you to “Light” (good) corporate governance.

Huh?

Let’s be honest. Most of us (understandably) don’t want to invest the time into learning good corporate governance. It’s really boring. But by showing you the (much more alluring) “Dark Arts”, you will also learn good corporate governance in the process.

This is the trade-off I’m willing to make to get more people exposed to good corporate governance. In fact, trade-offs are a recurring theme in this series.

There’s a lot to cover so Part 1 of the corporate governance “Dark Arts” series will focus on the basics and high-level concepts that will lay the groundwork for more nuanced discussions later.

Corporate Governance “Dark Arts”

If you’re not familiar with the “Dark Arts” in Harry Potter, feel free to apply your own concept of “light” vs. “dark”. Whether that’s the Dark Side of the Force in Star Wars or something more practical like Black Hat vs. White Hat hackers, every field tends to have Dark Patterns available to practitioners that allow them to exert control and/or influence in their favor (and normally at the expense of others).

This does not necessarily mean the “Dark Arts” are illegal. Massive businesses have been built at the intersection of legal and unethical. That said, I regard the “Dark Arts” as generally corrupting to those who use it, and the corrupting nature of the practices is why I consider it “dark”. It’s hard to turn back once you’ve experienced the power and reward.

While regulators may not crack down on “dark” practices, be aware that society (and regulators) can change its mind very quickly. For instance, people forget options backdating was once considered a perfectly acceptable practice in Silicon Valley until the Wall Street Journal covered it, ignited public outrage, and practitioners were subsequently punished by regulators.

Side note: Ben Horowitz wrote an interesting post on why he didn’t go to jail when the options backdating scandal hit. Spoiler, having senior people with a strong moral compass and a willingness to speak up may save you from future trouble.

So what do I mean by corporate governance “Dark Arts”?

The OECD describes corporate governance as:

“…a set of relationships between a company’s management, its board, its shareholders and other stakeholders. Corporate governance also provides the structure through which the objectives of the company are set, and the means of attaining those objectives and monitoring performance are determined.”

If good corporate governance is about aligning and encouraging management to take actions that have a beneficial effect to all shareholders (and often extended to all stakeholders), the “Dark Arts” are actions that distort that alignment to primarily benefit insiders by giving them disproportionate control and/or influence over the governance process. (This is not the cleanest definition, but hopefully you will have a better understanding as we progress through the series.)

Many times, a “dark” action may seem aligned and doesn’t look like a “big deal”, but these actions compound into much bigger problems later on.

There are also rare occasions when a “dark” action appears egregious and misaligned near-term, but may in fact be the best action to address long-term issues.

This doesn’t mean break-the-law, but governance isn’t always straightforward. There are many grey areas and trade-offs to consider.

These trade-offs are most often found in compensation.

Compensation is the Canary

Note: I’ll be using “compensation” and “comp” interchangeably.

Compensation is the most important concept to understand when examining the corporate governance “Dark Arts”.

Why? Compensation drives company priorities and behaviors.

Compensation is also the primary battleground between “light” and “dark”.

A well functioning compensation program will prioritize metrics and objectives that:

Drive long-term alignment between stakeholders and management.

Cascades down the organization to drive appropriate behaviors.

Creates long-term value for shareholders.

A company’s comp structure is a great way to examine how a company prioritizes their capital allocation and long-term strategy. What are the metrics the Board is prioritizing? How does the Board compensate the team over time? Does the comp plan properly incentivize the right behaviors? Etc.

So why is compensation the canary?

Like a canary in the coal mine, compensation best practices noticeably die first when exposed to the noxious environment created by the “Dark Arts”.

Compensation is supposed to align interests and drive company priorities, but the reality is personal self-interest can and will seep into the comp committee’s process, killing best practices and distorting priorities.

Comp Committee Best Practices and “Dark” Actions

Fenwick & West has a pretty good overview of Compensation Committee Best Practices that I’m going to use as a reference document to explain how “dark” actions kill best practices.

I’m not going cover all the best practices, but these are the concepts I consider the most important to monitor:

Best Practice: Committee members should be truly independent (not “cronies” of management) and function as an independent force in determining compensation.

“Dark” Action: Management stacks the committee with allies/cronies that compromises independence and sway compensation decisions.

Best Practice: Avoid appearance of quid pro quo.

“Dark” Action: Quid pro quo occurs and the “currency” exchanged doesn’t have to be monetary. There are many ways to make a “horse trade” to benefit committee members in exchange for favorable compensation.

Best Practice: Measure company and executive performance by meaningful and measurable long-term criteria consistent with overall compensation philosophy.

“Dark” Action: Management or self-interested Directors can influence which performance hurdles are incentivized and steer the committee to their preferred metrics and strategy. These metrics can potentially be “near-term” biased and conflict with creating long-term value.

Best Practice: Actively monitor and assess potential risks that arise from the company’s compensation practices and policies, and disclose and/or mitigate such risks as necessary.

“Dark” Action: Management may withhold key information that would compel the committee to “course correct”.

Best Practice: Chairman should control agenda, timing and scope of meetings.

“Dark” Action: Comp committee chair is arguably the most powerful “independent” position on the Board, and can distort the power dynamics of the entire Board if a self-interested Director and/or management crony is comp committee chair. These distortions include back room deals and undisclosed quid pro quo arrangements which conflict with (and circumvent) governance processes and controls. Directors also risk getting steamrolled and/or handcuffed by “collegiality culture” if they attempt to push back.

Best Practice: Establish guidelines for equity grants to minimize perception of market timing. (Note: Best practice in my opinion is to grant equity after the release of material information. For example, if the company grants equity annually, equity should be granted to management after Q4 earnings and guidance for next year is announced and priced into the stock.)

“Dark” Action: Comp committee “market times” equity grant to benefit insiders. This includes changing grant timing, grant size, equity type, metrics, vesting schedules, etc.

Of all the “dark” actions, monitoring equity grants is the most important. In particular, pay extra attention to “spring loading” and “bullet dodging” behavior.

“Spring Loading” and “Bullet Dodging” Equity Grants

What is “spring loading” and “bullet dodging”?

Spring Loading: The company grants equity and then releases news that positively impacts the stock price.

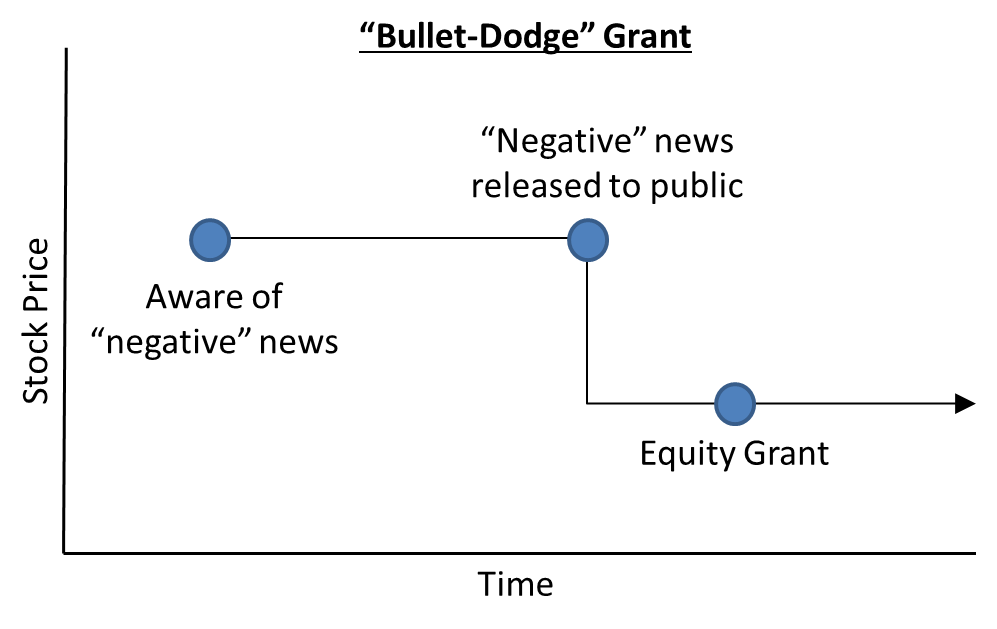

Bullet Dodging: The company releases news that negatively impacts the stock price and then grants equity.

Let these concepts soak in for a moment. There are companies that will “spring load” and “bullet dodge” equity grants to benefit insiders! If you can recognize the signs of this, you can profitably participate alongside. (Yes, I’m surprised this practice still exists.)

Why would companies engage in “spring loading” and “bullet dodging”?

There are a lot of reasons “why” this happens, but at the end of the day it’s a way to juice the value of equity granted to management. Some academics are calling the practice options backdating 2.0:

“Using conservative assumptions, Daines and his colleagues estimate that the new maneuvering provides an average extra payout of just over $100,000 per CEO. That’s above and beyond their salaries and the official value of their options.”

If you’re unfamiliar with the equity compensation and granting process:

Comp committee determines “target value” of equity to grant. (i.e. $100,000 target value)

The number of shares granted to management is determined by the stock price on the grant date. (i.e. $100,000 target value for restricted stock divided by $100 per share grant date stock price equals 1,000 shares granted to the executive.)

Manipulating the timing of grants relative to material news releases is an easy way for insiders to capture value in excess of “target value” (via underpriced stock by “spring loading” or acquiring more shares by “bullet dodging”). By the way, this isn’t exactly rare behavior:

“Daines and his colleagues found a remarkable telltale V-shaped pattern in stock prices when they analyzed 1,500 companies that granted options. On average, share prices dipped markedly in the 90 days before a grant and quickly began rebounding immediately afterward.

In effect, this pattern allows top executives to buy low and sell high. It’s not quite as risk-free as the original [options backdating] scheme, but it comes close. And it doesn’t appear to be a coincidence.”

“In the 90 days before the option grant, the average stock generated what analysts call an “abnormal negative return” of 1.9% — that’s a return 1.9% below those on shares of comparable companies during that same period. In the 90 days after the option grant, however, the average stock generated an abnormal positive return of 1.1%. Overall, the researchers estimate, the “round trip” from the temporary dip through the rebound produced an abnormal positive return of about 2%.”

How in the world is this legal?

The rules aren’t clear (SEC has not made it a priority to crack down), but I tend to agree with the scholars who view this activity as a form of insider trading.

Although the SEC has not taken a clear stand on the issue, the legality or illegality of spring-loading, specifically relating to insider trading rules, has been debated by scholars.

Professor Iman Anabtawi, for example, argues that spring-loaded options can be considered as discounted options. She states that “granting a stock option with an exercise price that does not reflect favorable inside information is substantively equivalent to granting a discount option; that is, an option with an exercise price below the market price on the date of the grant.

The upward price adjustment that results from the release of the inside information is the size of the discount.” Therefore, spring-loading and backdating may be different in form, but are largely the same in substance. Anabtawi further argues that “[w]hile it is true that using discount options may be efficient compensation policy, doing so without adequate disclosure to shareholders involves making materially misleading statements in connection with a securities transaction − in other words insider trading.”

At the very least, if the practice is not illegal, Directors (in my opinion) are breaching their fiduciary duties by allowing it to occur. A part of me suspects many Directors have no idea it’s happening under their watch.

Materiality Poker: Reading the Comp Committee (Chair) for Profit

If the SEC is not going to crack down on “options backdating 2.0” and academics believe the practice is prevalent, equity grants becomes a game of “materiality poker”.

Changes in compensation and grant timing are “tells” (to borrow a poker term) so it’s important to understand the “why” behind those changes. Usually the changes means nothing, but occasionally it hints to something very material.

If you can correctly read the motives of the comp committee (chair) and recognize a material “spring load” or “bullet dodge” is happening, you can trade alongside management’s greed and profit.

So with that in mind, shall we fold, call, or raise?

Up Next: Case Studies

Now that you have the high level concepts down, the rest of the series will focus on real world case studies. See you at part 2 soon!

Isn't it better to focus on the teams that don't do this and give them a premium versus try and trade around these catalysts?