The Impact of Misaligned Incentives

Case Study: How misaligned incentives at CoreLogic led to an activist confrontation

Welcome to the Nongaap Newsletter! I’m Mike, an ex-activist investor who writes about tech, corporate governance, the power & friction of incentives, strategy, board dynamics, and the occasional activist fight.

If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, I hope you consider joining me on this journey.

Disclaimer

Former Relational Investors (my old firm) Managing Director Jay Winship was recently elected to the Board of CoreLogic following a contested Special Meeting.

This write-up is entirely my opinion and analysis. I was not influenced nor encouraged to write this, and have not spoken to anyone involved.

Summary

This write-up is about misaligned incentives and how it can impact decision-making, strategy, and stock performance:

Misaligned incentives left unchecked can lead to years of lagging performance and shareholder frustration as insiders are insulated from the (financial) consequences of poor and/or self-interested decision-making and execution.

The appearance of misaligned incentives can be the first sign there are fundamental issues/challenges with management’s strategy, and serves as a “canary” for shareholders to exit (or proactively course correct) before it starts to materially impact stock performance.

Unwinding misaligned incentives can often lead to exceptional stock performance as the market removes the “misalignment discount” and re-prices the stock for “shareholder aligned” decision-making. This is why activists are attracted to these situations.

Misaligned incentives can be a two-way street and investor-specific incentives can cause misalignment by pushing companies to adopt rigid “investor friendly” incentives that diverge from long-term business priorities. This can be an especially material issue when a business and/or the underlying industry is undergoing a meaningful pivot/inflection and investors are reluctant to embrace the necessary changes.

No incentive structure is perfect. Getting incentives “right” is an iterative process that requires judgement and a certain degree of flexibility.

The easiest way to understand the dynamics of misaligned incentives is to walk through a real example.

CoreLogic Case Study: I walk through real estate data and analytics provider CoreLogic (ticker: CLGX) and their recent proxy fight with activist group Cannae Holdings (led by Bill Foley) and Senator Investment Group.

Hopefully this case study demonstrates how years of misaligned incentives impacted decision-making, insulated management from poor performance, and eventually led to an activist confrontation.

If you can identify and understand how misaligned incentives can impact decision-making and value creation, you’re going to do well as an investor.

Note: West Point grad Bill Foley has an affinity for naming his ventures after battles involving Hannibal. The battle between Cannae Holdings and CoreLogic has been interesting to follow.

Misaligned Incentives

Generally speaking, misaligned incentives are incentives that allow, encourage, and reward decision-making that destroys/erodes long-term value.

For example, to encourage M&A, the compensation committee may shift management’s primary compensation metric to adjusted EPS, and create a situation where management is handsomely rewarded pursuing M&A to grow adjusted EPS regardless of actual value creation.

Another example is the compensation committee excludes key financial metrics or hurdles from executive compensation which insulates management from the consequences of not achieving publicly stated “North Star” targets (i.e. “30% EBITDA margin”, “double digit organic revenue growth”, etc.). This can lead to sluggish returns since Boards are less likely to intervene if they’re not explicitly tracking these metrics and discussing them within the context of executive compensation.

Other misalignment “flags” include:

Board practices corporate governance “dark arts”

Payouts consistently outperforms (lagging) stock performance

Performance targets are set meaningfully below guidance or key benchmarks

More subtle “flags” (which requires judgement to determine if it’s a “flag”) include:

Using overly broad/easy-to-achieve financial metrics

Lack of capital returns as a compensation metric

Not tying a component of compensation to a multi-year operating plan

Incentive structure requires too much year-to-year micromanagement by the compensation committee to “work”

When you examine a company for misaligned incentives, keep in mind that no incentive plan is perfect and you should expect some level of (passive) misalignment. There are trade-offs to every plan and seeing misaligned incentives does not mean value destruction/erosion is going to happen.

It’s not uncommon to see incentive plans with glaring misalignment risk (especially around large M&A), but investors can trust management and the Board to be disciplined (due their track record) and use their judgement to avoid truly value destructive outcomes.

That said, it’s important to acknowledge Boards can and will actively structure compensation to disproportionately benefit/insulate insiders and their preferred strategies at the expense of shareholder interests.

It is this intentional, self-serving misalignment that investors must be vigilant about.

How Misaligned Incentives Coalesce

You’d think misaligned incentives is the result of corrupted corporate governance, but I’d say the number of instances where I felt truly bad actors drove misaligned incentives is quite small.

In most cases, misaligned incentives coalesce under the oversight of Boards with “good” intentions. What happens is compensation committees make iterative adjustments to incentives (that appear “fair” and reasonable) which eventually compound into a materially misaligned situation.

The incentive setting process is a lot like a flywheel (sorry, but I had to):

Ideally, Boards are objectively making adjustments to incentives based on the outcomes they’re measuring to encourage decision-making that drives long-term value. The issue is compensation committees are run by humans which means they’re susceptible to influence and self-interest when setting incentives. This means the incentives and outcomes can decouple.

Management, who has disproportionate influence in this incentive setting process, is going to (rationally) advocate for themselves and push for incentives that maximize their risk-adjusted compensation. Their advocacy can lead to misaligned incentives, because maximizing risk-adjusted compensation often entails minimizing exposure to bad outcomes. Put another way, executives want to get paid regardless of outcome.

Beyond management, investors and other stakeholders can also influence the incentive setting process and advocate their own misaligned incentives that erodes long-term value creation.

Getting incentives “right” is an iterative process that requires judgement and a certain degree of flexibility. Misaligned incentives is like the “technical debt” of the incentive setting process. We don’t want it, but it’s going to happen. The goal is really to manage misaligned incentives so it doesn’t hurt the company instead of trying to eliminate it (which is arguably impossible).

Investing in Misaligned Incentives

The impact of misaligned incentives can be quite material to shareholder returns.

Generally speaking, misaligned incentives left unchecked can lead to years of lagging performance and shareholder frustration as insiders are insulated from the financial consequences of poor and/or self-interested decisions-making, and don’t have the sense of urgency to make changes.

In my experience, misaligned incentives often represent the first signs there are fundamental issues with management’s strategy, and can serve as a “canary” for shareholders to either exit or proactively engage to course correct before misalignment starts to materially impact the stock price.

For instance, the Board may “lower the bar” on incentive targets and pay management handsomely for hitting the low end of publicly stated guidance when previous targets required hitting the high end of guidance.

Lowering the bar doesn’t seem like a major issue, but it’s often the “tip of the iceberg” of bigger underlying issues. When you start digging into why the bar was lowered, more often than not it’s not a pretty picture.

Remember, management is going to advocate for themselves during the compensation setting process and push for incentives that maximize their risk-adjusted compensation. If their preferred strategy isn’t producing results (yet…it’s always just around the corner!), they’ll push for adjustments to compensation to ensure they’re still paid.

Instead of the incentives course correcting management, management is course correcting the incentives.

Markets are initially slow to react to these incremental changes, but will quickly apply a “misalignment discount” (i.e. assumes punitive capital allocation) once it’s clear the issue will persist and there’s no desire to remedy it. If corporate governance is the achilles’ heel of companies, misaligned incentives is what eventually “snaps” it and causes a company’s valuation to crumble.

That said, if the Board changes course and unwinds a misaligned incentive structure, this can lead to exceptional stock performance as the market removes the “misalignment discount” and re-prices the stock for “shareholder aligned” decision-making. This is why companies with misaligned incentives can be a good place for activism (or constructivism).

Overall, companies with misaligned incentives can be a terrific source of investment opportunities (long and short).

Case Study: CoreLogic

The easiest way to understand the dynamics of misaligned incentives is to walk through a real example.

For the rest of this write-up, I’m going to walk through real estate data and analytics provider CoreLogic (ticker: CLGX) and their recent proxy fight with activist group Cannae Holdings (led by Bill Foley) and Senator Investment Group.

Hopefully this case study demonstrates how years of misaligned incentives impacted decision-making, insulated management from poor performance, and eventually led to an activist confrontation.

For those not familiar with CoreLogic, think of them as the gold standard of property data in the U.S. (and a handful of other international markets). They have near-census coverage of property parcels and structures in the U.S., and touch 7 out of every 10 mortgages originated in the U.S.

The company also provides market intelligence products such as home price indices, and risk management products such as weather modeling for the insurance market.

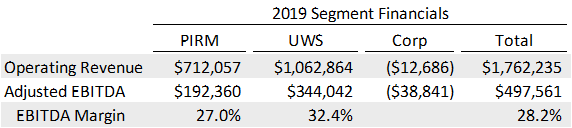

Note: Property Intelligence & Risk Management (PIRM) houses their market intelligence and risk management products, and Underwriting & Workflow Solutions (UWS) houses CoreLogic’s major U.S. mortgage operations.

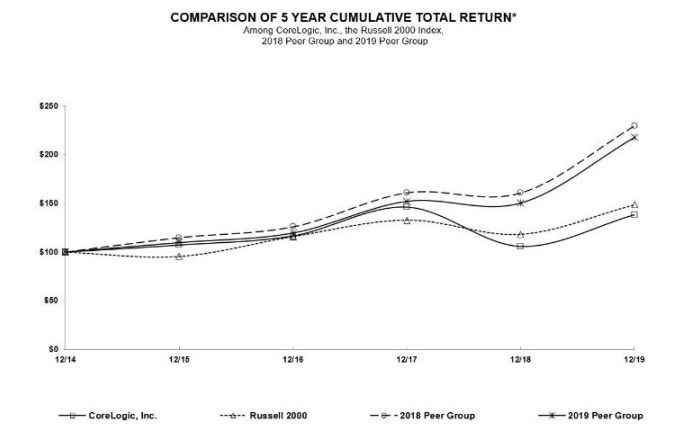

Since spinning out of First American Financial 10 years ago (June 2010), I’d characterize CoreLogic’s public market run (pre-activist involvement) as mediocre/challenged:

The core property data business is very good, but beholden to U.S. mortgage originations so it’s volatile with limited growth/addressable market expansion opportunities.

Consequently, to really “work” as a public standalone company, the company (arguably) needs a best-in-class capital allocator to re-deploy excess capital from the property data business.

Without a top notch capital allocator, CoreLogic is susceptible to underperforming proxy peers who objectively have better businesses and growth prospects.

When you examine CoreLogic’s capital allocation the past decade, it becomes evident they’re not great capital allocators which have contributed to lagging performance versus proxy peers.

Normally, shareholders can exert pressure to drive appropriate changes (including strategic alternatives), but First American Financial had a “right of first refusal” on any takeouts of CoreLogic as part of its spin-off agreement which insulated the company from external pressure.

I believe CoreLogic would have been acquired years ago if there wasn’t a “right of first refusal” in place, and it’s not a coincidence an activist showed up with a hostile bid the moment it expired on June 1, 2020, and is now in a strategic review process.

So what happens when insiders get a 10-year run with limited shareholder pressure and are poor capital allocators?

Misaligned incentives become a prominent and intentional part of compensation as management seeks to get paid regardless of shareholder returns.

Years of Misaligned Incentives at CoreLogic

If you read my G.O.V.E.R.N. Framework piece, you may recall I feature CoreLogic as an example of misaligned incentives, and highlight how performance hurdles set by CoreLogic’s Board produced terrific payouts for management despite lagging stock returns.

Specifically, the Board rewarded CoreLogic management with generous 130%+ payouts on performance-based RSUs using (in my opinion) easy-to-achieve adjusted EPS targets:

During the same performance period CoreLogic insiders were getting paid 130%+ equity payouts, the company materially lagged their compensation peer group:

Whenever you see a situation where management is achieving “above target” payouts for performance that is meaningfully lagging their proxy peer group, it’s safe to assume there are issues going on at the company.

For CoreLogic, the issue was management’s pursuit of an M&A centric strategy to drive growth and diversify away from (volatile) U.S. mortgage originations wasn’t generating commensurate shareholder returns.

Instead of recognizing the strategy wasn’t generating acceptable returns for shareholders and course correcting, the Board structured compensation to disproportionately pay management and insulate them from the consequences of their M&A strategy.

When you really dig into the performance-based grants, the misalignment with shareholders is pretty egregious:

Adjusted EPS is used as the primary financial hurdle which encourages M&A while ignoring the consequences of capital destructive deals.

Using adjusted EPS also makes it possible to beat EPS targets by repurchasing shares in case profit growth projections fall short. Management using buybacks to get paid instead of applying it within a proper capital allocation framework is why share repurchases get a bad rap.

To accommodate the lumpy/volatile nature of mortgage originations, the plan also uses an “either or” approach to maximize management’s payout. Getting compensated on either three 1-year targets or a cumulative 3-year target adds a lot of complexity to the incentive setting process and makes oversight harder. It can confuse even the most thoughtful investor and/or director.

Don’t believe me?

The table CoreLogic uses in their 2020 Proxy to summarize 2019 performance for 2019 performance-based grant is wrong and mixes up targets from prior grants:

Yes, the company can say the error is just a typo, but there’s something to be said about having a simpler compensation structure so it’s easier for directors and investors to quickly recognize there’s an error. Complexity favors the self-interested.

Where things start getting egregious (in my opinion) is the path to achieving “above target” payouts is very easy:

If management beat adjusted EPS target by 5%, they receive a 125% payout

Beat the target by 10% and management receives a 150% payout

Beat the target by 20% and management receives 200% payout (maximum)

So when you see CoreLogic’s management team is receiving 130%+ payouts on performance-based RSUs, they’re basically beating adjusted EPS targets by 6%+.

Is that a fair compensation outcome when the stock consistently lags their peer group the past 10 years? I’d say no.

The Board and management team may push back and say there’s a TSR modifier, but it lacks teeth and doesn’t drive shareholder aligned behavior (which is the point of TSR hurdles).

Furthermore, to maximize the odds management gets paid “above target”, the Board started to set targets at the low end of public guidance:

CoreLogic’s Board went above-and-beyond to pay management for no performance.

This egregious misalignment with shareholders would eventually attract Bill Foley who recognized CoreLogic was very mismanaged and had a lot of untapped value.

Bill Foley at the Gate

It’s not often you get to critique a 1980s style hostile takeover attempt, but that’s the situation we had at CoreLogic earlier this year.

But instead of Barbarians at the Gate, it’s Bill Foley at the Gate with Bill Foley’s Cannae Holdings and activist hedge fund Senator Investment Group pursuing a $65 per share hostile acquisition of CoreLogic.

For those unfamiliar with Bill Foley, he’s considered an “outsider” executive, operator, and dealmaker. He’s highly regarded by investors for his 30+ year track record of delivering shareholder value, having built several multi-billion dollar public companies via M&A (100+ acquisitions under his belt) and spin-offs.

Bill Foley is best known for serial acquiring companies at Fidelity National Financial (ticker: FNF) where he grew the company from a small local title insurance operation in the early 1980s into a Fortune 500 company today.

Through FNF, he also built/acquired and spun-off several public companies including FIS Global (ticker: FIS), Black Knight (ticker: BKI), Ceridian (ticker: CDAY), J. Alexander (ticker: JAX), and Cannae Holdings (ticker: CNNE).

Bill Foley’s value creation playbook is pretty straightforward and exactly what CoreLogic needs:

Basically, Bill Foley’s playbook is an outline for driving alignment with shareholders which is the opposite of what CoreLogic insiders have done.

Given Bill Foley’s extensive M&A history and deep familiarity of the mortgage originations market, it’s no surprise he’d be interested in acquiring CoreLogic.

The Battle of CoreLogic

The battle for CoreLogic has been fun to follow and featured some interesting tactics from both the activist group and Corelogic’s activist defense team.

Much of the activist campaign centered on highlighting issues that the Board was proactively insulating management compensation from:

It’s pretty hard to credibly defend an activist’s talking points when there’s a multi-year track record of the Board adjusting compensation to protect executive pay from those same talking points. Interestingly, the activist group doesn’t even mention the role misaligned incentives played in all of this.

After much back-and-forth, the activist group would announce the withdrawal of their hostile bid following CoreLogic’s announcement they were engaged in acquisition talks with third parties that valued the company at or above $80 per share (which is ongoing).

Despite dropping their hostile bid, Cannae and Senator would still proceed with their activist campaign to remove CoreLogic directors at a November 17, 2020 special meeting and successfully elected 3 dissent directors to the Board.

It’s amazing how differently CoreLogic conducts itself as a public company (i.e. aggressively raising targets, running strategic review, etc.) when an activist shows up and forces re-alignment with shareholders.

Parting Thoughts: Do Your Own Due Diligence

Because misaligned incentives can materially impact decision-making and stock performance, I believe it’s important for investors to do their own due diligence on identifying and understanding misaligned incentives.

The proxy advisors (i.e. ISS and Glass Lewis) that institutional investors typically rely on for compensation analysis don’t monitor this dynamic very well (in my opinion). They’ll certainly review the consequences of misaligned incentives in a contested election, especially if an activist lays it out for them, but you shouldn’t expect them to preemptively flag misalignment for you.

Frankly, it’s not fair to expect proxy advisors to catch misaligned incentives. Properly identifying and assessing misaligned incentives requires having an investor perspective to integrate operational and strategic considerations to add context and nuance to compensation analysis. The proxy advisors aren’t optimized for this.

Case in point, CoreLogic shareholders overwhelmingly approved CoreLogic’s executive compensation (“say on pay”) at the April 2020 Annual Meeting despite the plan being egregiously misaligned.

Fast forward to the November 2020 Special Meeting, and the proxy advisors are criticizing the company for failing shareholders and recommending dissident directors to facilitate changes.

This abrupt swing in sentiment is not surprising. You’d think the voting results of the Annual Meeting is a useful signal of shareholder sentiment and an endorsement of the company’s strategy and compensation plan, but that’s not really the case.

Most funds will defer their voting decisions to what the proxy advisors recommend, and these advisors take a fairly formulaic approach to proxy vote recommendations. They’re not going to examine important issues like misaligned incentives unless it’s brought up in a contested election.

This deferential voting dynamic also means shareholder frustration is typically not reflected in the votes unless the situation gets egregiously bad. This can lead to misaligned incentives persisting for years, and disproportionately influencing the company’s decision-making and subsequent stock performance until things blow up and/or an activist arrives.

When you examine the activist fight at CoreLogic, many of the issues flagged by the activist group (Cannae and Senator) were (in my opinion) the result of CoreLogic’s misaligned incentive structure facilitating years of poor capital allocation decisions and no sense of urgency.

Had the proxy advisors and shareholders recognized this misalignment, they could have attempted to address these issues years ago. Instead, an activist had to show up with a hostile offer to force changes.

Do your own due diligence.

Hi Mike, great analysis. Love the blog.

Do you think CLGX will be teken out at >$80?