Would You Like To Add Tax With That?

How DoorDash's Breakthrough Unit Economics May Break The Company

Welcome to the Nongaap Newsletter! I’m Mike, an ex-activist investor, who writes about tech, corporate governance, the power & friction of incentives, strategy, board dynamics, and the occasional activist fight.

If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, I hope you consider joining me on this journey.

Update: Welp, I got scooped by the WSJ and Recode on the food delivery sales tax issue, but the show must go on.

Flying Too Close To The Sun

Sometimes you come across a situation and wonder:

“Either this is malpractice by insiders and investors or they knew about the issue and opted to stay the course anyway.”

DoorDash and the financial & mental gymnastics required to make their food delivery unit economics “work” is one of those situations.

Note: I’ve always preferred DoorDash’s “winged” logo over the current iteration. Amusingly, this post is about DoorDash “flying too close to the sun”.

TLDR Summary

U.S. food delivery is a highly competitive space and frankly a “shitty business” where subtle changes in unit economics can drive massive changes in value.

Because of the economic upside available to the ultimate winner(s), there’s incentive to push the envelope to win.

DoorDash’s breakthrough unit economics allowed the Company to separate itself in a crowded market and drive incredible market share gains by: 1) offering competitive prices despite charging a service fee, 2) lowering out-of-pocket delivery expenses, and 3) redeploying freed up capital to improve restaurant & driver networks.

Despite making adjustments in response to consumer, media, and government push back, the Company still faces potentially material liabilities tied to their sales tax and gratuity practices as well as increased competition from Grubhub who is intent on removing/minimizing levers DoorDash has utilized to grow.

Speculative Hot Take: An argument can be made that gratuity paid under DoorDash’s “guaranteed minimum” pay model could/should be treated as a “service charge” for tax and driver income reporting purposes.

Finally, DoorDash has the added challenge of addressing these issues while simultaneously trying to solve the gordian knot that is their cap table to continue funding operations.

I Like DoorDash

I actually like DoorDash. I really do.

Food delivery sucks, and it requires a ton of work and execution to accomplish what Tony Xu and team has done in the space. Most food/restaurant tech companies go bust or pivot to sneakers.

In general, I believe the best executing companies tend to bubble up (no pun intended) in markets with tight margins. You either execute or get executed by competitors.

When you consider the margin challenges of food delivery, DoorDash belongs in the conversation of top executing companies.

Unfortunately, somewhere along the way, I believe leadership did not get good advice (or maybe they didn’t listen) on some of their “push the envelope” decisions on unit economics and fundraising.

For those interested, I did a tweet storm on the power of relationships on corporate governance and doing the “right” thing:

Food Delivery Sucks

The knife fight currently going on in the U.S. food delivery space between Grubhub, DoorDash, Postmates, and Uber Eats is fascinating to follow. It’s a messy battle characterized by aggressive market/pricing behavior and a general disregard for profitability to drive market share gains.

It’s occasionally petty:

Simply put, food delivery sucks. Restaurants can only pay so much given their margin structure. Drivers expect market competitive compensation. Consumers are sensitive to excessive fees. There’s not a lot of profit to go around.

In the past, Grubhub’s CEO Matt Maloney described food delivery as a “shitty business”:

"I'm running my delivery-based business with the explicit goal to break even," Maloney says. "That's not fun for me, and normally I'd say that's the dumbest business you could ever be in. Why run a break-even business? That's a pain in the butt."

In this “food delivery sucks” backdrop, the space is a great place to study unit economics and competitive dynamics given minor differences in price can sway promiscuous diners from one service to another, rapidly wiping out and ramping valuations in the process.

DoorDash’s Meteoric Rise

It’s hard to understate just how impactful changes to DoorDash’s driver pay model was to their delivery unit economics and scaling.

DoorDash went from grinding on growth & valuation (mind you still successful!) to a Company that unlocked food delivery’s “shitty business” puzzle and turned into a valuation and market-share-gaining rocket-ship within a relatively short period of time.

As Warren Buffett once famously said:

"When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact."

And yet, DoorDash overcame a business with a reputation for bad economics.

How did they do it?

Breakthrough Unit Economics

1. Consumers Want & Demand Competitive Prices: DoorDash Delivered

If you believe Washington D.C. Attorney General Karl Racine, DoorDash achieved competitive prices by pocketing customer gratuities meant for drivers and lowering delivery fees charged to customers.

If you believe Grubhub CEO Matt Maloney, the answer is primarily not paying sales tax. The debate on sales tax is still playing out in real-time and DoorDash’s public position is currently “no comment”, but something has to give.

DoorDash and Grubhub are offering identical delivery services often times for the same restaurant and yet we’re looking at potentially ~$0.50 or more difference in sales tax collection per transaction. $0.50 per transaction turns into massive numbers (and liabilities for DoorDash if they under collected sales tax) when you roll it up.

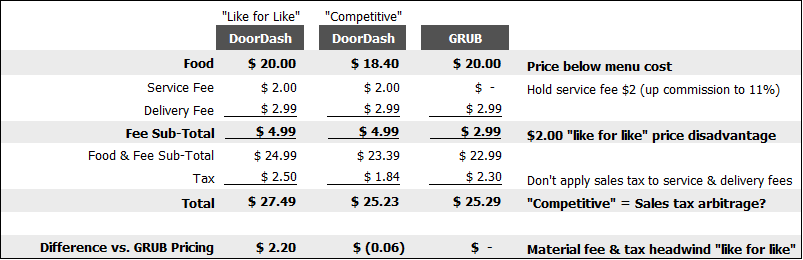

That all said, to better understand competitive pricing dynamics, let’s take a look at a hypothetical “like-for-like” transaction for DoorDash vs. Grubhub assuming 10% sales tax (shout out to Los Angeles!) with sales tax is applied to fees, and the general adjustments required to be “competitive”:

The first thing that sticks out is DoorDash’s service fee (typically 10%+ of food costs) which puts them at a price disadvantage out-of-the-gate.

How does DoorDash overcome a 10%+ structural cost disadvantage?

The difference in sales tax is well covered and a major contributor, but DoorDash can also charge below menu prices which creates a subtle “sales tax arbitrage” (when applying their sales tax methodology) to lower costs.

Previously, DoorDash would include their service fee within the cost-of-food as a mark-up to menu costs. Customers would in turn also pay sales tax on the marked-up food.

Using the hypothetical “like-for-like” transaction above, adding a $2.00 mark-up to food would also add $0.20 to sales tax. Alternatively, reducing food costs $2.00 and moving it to service fee can save consumers $0.20 in sales tax according to DoorDash’s sales tax collection policies. That can be the difference between picking DoorDash over competitors who bury fees within food costs.

Interestingly, when DoorDash moved their service fee in 2016 to a separate line item, they (in my opinion) implied the benefit of “sales tax arbitrage” when discussing the benefit of a separate line item service fee in their announcement:

Now when ordering on DoorDash, customers pay for the price of their food and any local taxes, plus a delivery fee, an optional Dasher tip and a service fee. The service fee is simply our way of breaking out existing fees that were previously built in to menus and providing more information about how orders are priced. The change should not significantly impact the overall price of ordering on DoorDash and does not affect delivery fees. While some people may see orders with higher total charges, on average we expect that ordering from DoorDash will actually cost less with this change.

At this point, you may be saying “This is just a hypothetical example!” so let’s use a real world example to drive the point home.

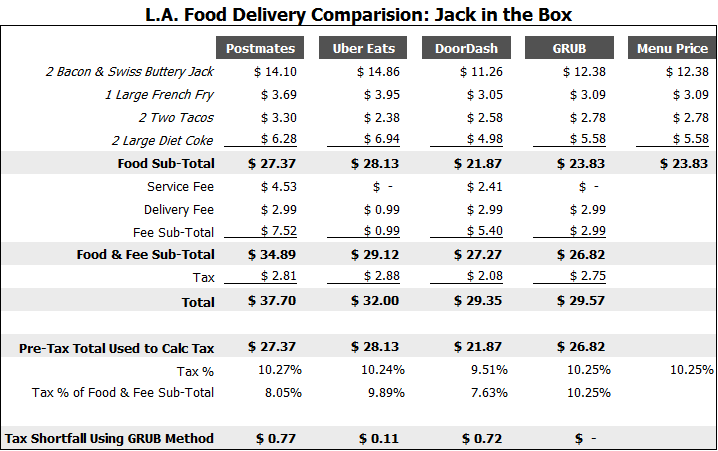

Here is what the various food delivery platforms actually charge customers for a Jack in the Box order in Los Angeles:

There’s a lot going on here so let’s highlight some key takeaways:

Grubhub is the only food delivery provider charging menu prices with no service fees. Seriously, I visited Jack in the Box and took photos to confirm menu prices!

Remember the hypothetical example we discussed of DoorDash shifting $2.00 in food costs to service fees in order to lower sales tax exposure vs. competitors? They are literally doing it here in an actual example.

Postmates, Uber Eats, and DoorDash take different approaches to “price gouge” consumers with additional fees. Postmates splits their fees between hidden food mark-ups and standalone fees (yikes that’s a lot of fees). Uber Eats shows no service fee and aa low delivery fee, but hides meaningful fees via food mark-ups. DoorDash uses their service fee to “offset” their discount to menu price.

Despite Grubhub having the lowest pre-tax sub-total, DoorDash ends up with the lowest total order cost after accounting for lower taxes due to: 1) applying the incorrect 9.5% tax rate instead of 10.25% (which is another liability DoorDash must address in key markets), and 2) not applying sales tax to service and delivery fees.

Maybe I’m whining, but it’s mind-boggling Postmates charges the most and may still have a material liability tied to under collecting sales tax. (Los Angeles is a major market for them)

Finally, where does Jack in the Box stand in all of this? 4 identical orders with 4 completely different prices and sales tax totals. Who is remitting the sales tax?

So there you have it. Despite a structural service fee disadvantage, DoorDash is able to offer competitive prices to Grubhub’s no-service-fee model.

2. Drivers Demand Competitive Compensation & the Company Needs Reliable Supply of Drivers to Fulfill Orders: DoorDash Found the Tipping Point to Unlock Capital & Driver Network Reliability

There’s a ton of coverage related to DoorDash’s infamous gratuity model which was subsequently revised, but it’s still worth examining given its impact (in my opinion) improving & scaling driver network, lowering out-of-pocket delivery costs, and freeing up capital to aggressively invest in pricing & platform.

For those out-of-the-loop, the “Guaranteed Minimum Pay” model was officially implemented September 2017 after months of testing:

For each delivery, the Dasher will always receive at least $1 from DoorDash plus 100% of the customer tip. Where that sum is less than the guaranteed amount, DoorDash will provide a pay boost to make sure the Dasher receives the guaranteed amount. Where that sum is more than the guaranteed amount, the Dasher pockets the extra amount. In addition, each market has a minimum floor that Dashers will make on every delivery no matter the complexity ($6.00 in most cases).

The pay model was conceptually brilliant:

Drivers, in general, want a minimum payout to fulfill an order (typically $6.00). DoorDash offers a “guaranteed minimum” that meets the pay hurdle to ensure a driver will fulfill the order.

If a driver is paid below their expectations (i.e. $6 per delivery), they will eventually churn off the platform. If DoorDash discloses too much payout information, drivers will “cherry pick” the highest paying orders and limit DoorDash’s ability to fulfill lower paying orders. “Guaranteed minimum” blurs pay to ensure a reliable & liquid driver network is available to fulfill all DoorDash orders.

The pay model (by my rough estimation) also lowered DoorDash’s out-of-pocket delivery fee expenses. Assuming customer tip distribution of 15% (no tip), 45% (tip half of guaranteed minimum), 40% (tip full guaranteed minimum), the blended per delivery out-of-pocket cost to DoorDash is ~$2.50 to ~$3.50 on a $6.00 to $8.75 per delivery driver payout. That’s a material cut in delivery costs considering the original 2013 delivery fee to customers was $6 per delivery and 2016 driver payments ranged from $5 to $8 per delivery before tips. Instead of charging customers $5 to $6 in delivery fees, DoorDash can now meaningfully cut delivery fees charged to customers ($1.99 to $2.99) and offer very competitive prices without losing money on the delivery.

While “tip pooling” is not possible, DoorDash introduced the concept of tech-enabled “delivery fee pooling” (at least that’s what I’m calling it). The delivery fees charged to generous tippers were reallocated to no-to-low-tip deliveries.

The pay model should have never been implemented:

It doesn’t pass the smell test and someone should have asked “Is this really legal?”.

For the model to work, it requires disguising the true payout to drivers and turning negotiations into a pseudo loot-box (keep doing deliveries and one of them might have a big payout!) instead of a true arms-length negotiation between DoorDash and the independent contractor. DoorDash knows exactly what a customer tips (and ensured they knew by removing post-delivery in-app tipping in February 2018) when a customer places an order. This is a massive info advantage when pricing the “guaranteed minimum” amount.

The model is also deceptive to customers, takes advantage of tipper goodwill, and common sense says the policy would be brand destroying long-term.

3. The Unit Economics Must Work: Pushing the Envelope on Sales Tax & Gratuity Created a Rocket Ship

Following the implementation of the “guaranteed minimum” pay model, DoorDash nearly triples its valuation in 5 months to $4 billion and announces they are contribution margin positive:

“As a company, we are contribution margin positive. We’ve been that way for six straight quarters now, which means we pay off all of our variable expenses and all that’s left are the fixed costs” - DoorDash CEO, Tony Xu (August 2018)

DoorDash turned a “shitty business” into a rocket ship. Now what?

Will DoorDash's Breakthrough Unit Economics Break the Company?

It’s not hard to be concerned about DoorDash’s sales tax practices and potential liabilities when Grubhub CEO Matt Maloney is publicly saying:

“We have been audited by multiple states, multiple times, and in every case we were required to collect and remit sales tax on delivery fees.”

Is Grubhub right? Time will tell, but clearly Grubhub is out for blood and wants to force the issue on sales tax.

Even if Doordash is in the clear, the Grubhub is going to “course correct” on the sales tax issue and any sales tax related advantage DoorDash may have had over Grubhub in the past will eventually be removed going forward, putting a spotlight on DoorDash’s structural service fee cost disadvantage.

Further, Grubhub has indicated a willingness to go “all in” and aggressively compete in food delivery (slashing their public market valuation in the process) at a time competitors are looking to rationalize or an exit.

Overall, DoorDash CEO Tony Xu has built a huge, successful company which is incredibly hard to do and warrants celebration, but he also has to deal with a Gordian Knot of a cap table to raise more capital when all competitive signs and potential past liabilities point to a massive down round.

DoorDash’s breakthrough unit economics gave them the wings to soar, but the Company may have flown too close to the sun.

Extra Hot Take: DoorDash’s “Guaranteed Minimum” Pay Model Makes Me Wonder If “Gratuity” Is Actually A Service Fee.

I keep reading the IRS explanation of what a tip/gratuity is and a part of me wonders if DoorDash’s “guaranteed minimum” pay model accidentally turned gratuity into a service fee:

Four factors are used to determine whether a payment qualifies as a tip. Normally, all four must apply. To be a tip:

The payment must be made free from compulsion;

The customer must have the unrestricted right to determine the amount;

The payment should not be the subject of negotiations or dictated by employer policy; and

Generally, the customer has the right to determine who receives the payment.

If any one of these doesn’t apply, the payment is likely a service charge.

The “subject of negotiations or dictated by employer policy” test throws me into a loop especially when you combine it with California’s sales tax test for delivery fees which states:

The portion of the delivery charge that is greater than the actual delivery cost is taxable.

Remember, if a customer is a generous tipper and covers the entire “guaranteed minimum” offered to a driver, DoorDash only pays the driver $1 instead of the full delivery fee (i.e. $2.99) charged to customers. This means the difference is subject to sales tax in California, and the customer’s tip amount has a direct impact on a customer’s sales tax liability.

Suddenly, the tip is subject to negotiation…right? It’s something to ponder.